The Aranda brings worrying news about the state of the Baltic Sea, yet the monitoring results are no surprise

Text:

The Aranda, a marine research vessel owned by the Finnish Environment Institute (Syke), regularly monitors the state of the Baltic Sea. In August, we were able to join the ship on a monitoring expedition to collect data on the biological, physical and chemical state of the Baltic Sea and concentrations of harmful substances. The data collected during monitoring expeditions is important for analysing things such as eutrophication, oxygen levels, plankton and benthic communities. August’s monitoring results indicate a long-term deterioration in the state of the Baltic Sea.

The sea stretches to the horizon in every direction – breathing peacefully with the waves that the wind sends rippling across the water. Yet the myriad tankers and cargo ships that we pass remind us of the Baltic Sea’s importance as a geopolitical hub. Ships criss-cross the water, while others are anchored in rows as they wait to enter port. In the distance, a Russian warship cleaves through the Gulf of Finland’s central channel backed by the slumbering shape of Suursaari island.

But the Finnish Environment Institute’s marine research vessel, the Aranda, has a very different mission in the Gulf of Finland: it shuttles from one measuring point to the next, scientifically mapping the state of the Baltic Sea. Continuous monitoring over many years provides long-term data on changes in the state of the Baltic Sea and the impact of land-based conservation measures on its wellbeing. This information is important not only for research and conservation organisations, but also for policymakers.

Ship is loaded with research

Syke undertakes several expeditions on the Aranda each year to survey the state of the Baltic Sea: in January, around Eastertime in the spring, in May/June and in August.

This August’s monitoring expedition was led by Maiju Lehtiniemi, a research professor from Syke, who was in charge of organising the expedition and carrying out sampling and research. The Gulf of Finland leg of the voyage involved 14 crew members and 15 researchers from Syke, the Finnish Meteorological Institute and a couple of universities.

They worked around the clock to make the most of their time at sea. Hundreds of water samples were collected during the expedition. Some were analysed onboard, while others had to wait until they reached a laboratory ashore. Bottom sediment was also sampled, and the sea’s physical properties were measured with wave buoys.

Monitoring results reveal the dire state of the Baltic Sea

Syke published the results of its August monitoring expedition on Baltic Sea Day at the end of August. The news about nutrient concentrations in Finland’s southern seas is bad: the amount of phosphate phosphorus, which causes eutrophication, has increased over the long term. Although nutrient emissions into the sea have been reduced, the Baltic Sea’s main basin still discharges anoxic and nutrient-rich bottom water into the Gulf of Finland. In August, the oxygen situation was also poor in deep-water areas of the Gulf of Finland.

Both nutrient and oxygen concentrations are affected by water stratification in the Baltic Sea: as saltier water is heavier than freshwater, it sinks to the bottom. The layers of water are also poorly mixed, which prevents oxygen from reaching deeper areas of the sea. Life is disappearing from deoxygenated areas: benthic animals are dying and fish are losing their habitats.

Eutrophication contributes to the deoxygenation of the seabed, as more and more dead algae cells sink down from the surface and are decomposed in deep waters by biological processes that consume oxygen. Anoxic seabeds will in turn release phosphorus into the sea, creating a vicious circle.

Water samples are taken from the depths of the sea

The Rosette water sampler finally reaches the surface and is guided onto the vessel’s research deck. Scientists from the laboratories come to collect samples for a broad range of purposes.

The sampler brings samples collected from the depths of the sea all the way to the surface: it is first lowered almost to the bottom, and is then lifted back the surface, stopping at predetermined depths along the way to take water samples.

The Rosette’s lower section contains a device (a CTD probe) that continuously measures a number of the water’s properties whilst the sampler is moving: temperature, oxygen concentration, salinity and chlorophyll a (which indicates the amount of algae in the water). It therefore provides a real-time profile of certain water properties throughout the water column, and the graphs drawn on the computer screen will immediately indicate the relations between the water’s properties as the depth changes.

One of those coming to the research deck to collect samples is marine analyst Tanja Kinnunen, who works in the chemistry lab and has also worked on the Aranda for about three decades. Kinnunen’s work includes measuring oxygen and nutrient concentrations in water.

Although we can now glide across the almost-calm surface of the Baltic Sea, Kinnunen’s career has included some stormy voyages.

In particular, Kinnunen recalls a 1995 expedition during which the Aranda was caught in a storm in the Gotland Basin while trying to sail to shelter on the east side of the island. Winds reached 44 m/s at times. However, the adrenaline rush caused by the storm helped to dispel any nausea felt by the scientists huddled on the sofas in the mess (the ship’s meeting, lounge and dining area). Nowadays, you do not knowingly head out into stormy waters to do science.

Long-term monitoring of the sea’s state

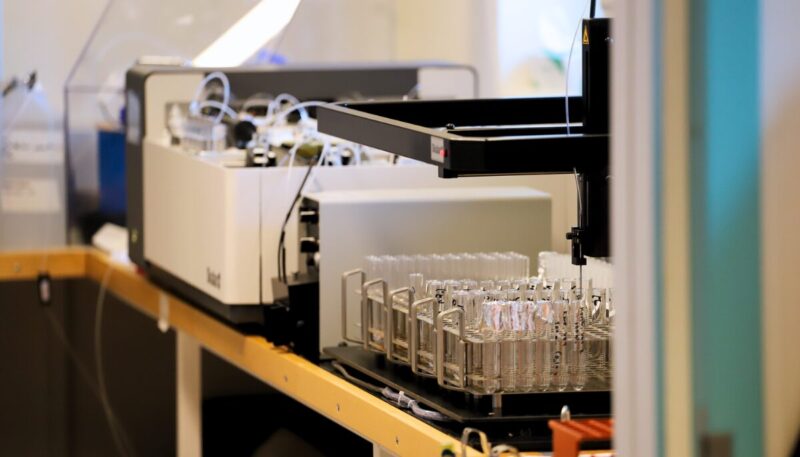

There’s an exciting-looking machine in one of the rooms in the chemistry lab. Water moves through its thin tubes, and also tiny air bubbles at regular intervals.

A nutrient analysis is underway, using a Skalar nutrient analyser, which has only been on the Aranda for a couple of years. Its results will indicate the volume of nutrients, such as phosphorus and nitrogen, that are available to algae in the water. The excessive growth of algae and aquatic plants causes eutrophication.

Pia Varmanen, who works with nutrient analyses, introduces us to the Skalar and its results. One point to note is that nutrient levels are high near the seabed – which is typical for August.

The results of the analysis will only be sent to the register once we are back on land and can get an uninterrupted internet connection. The results will also be crosschecked after the expedition: so all of the results will pass in front of several pairs of eyes. The expedition leader will be informed if any anomalies are detected during the voyage. Varmanen says that long-term monitoring work is rewarding in spite of the precision that it requires.

“Collecting data on the state of the Baltic Sea is important for understanding its condition and planning conservation measures. Continuous monitoring is an essential part of a broader process in which scientists are working together,” says Varmanen.

Information about food webs in the Baltic Sea

Near the chemistry lab, on the other side of the corridor, is the biology lab. Its walls are decorated with microscope images of a variety of plankton.

Phytoplankton samples are taken from the Rosette’s water samples, while zooplankton samples are collected from the sea using a large net. However, the analysis of these samples will only be carried out ashore.

The status of zooplankton and benthic organisms in Finnish seas has taken a turn for the worse in recent decades. The number of zooplankton in the sea has decreased, and a lack of oxygen on the seabed is making it difficult for benthic animals to survive.

However, the August monitoring expedition also gives us a small ray of hope: According to monitoring results published by Syke at the end of August, there seem to be more copepods in the Gulf of Finland’s open-sea community. Copepods are an important source of food for many fish. It is, however, too early to draw any major conclusions from these results. Continued monitoring over the coming years will confirm how the situation is evolving.

From research results to action

Before the ship arrives in the Port of Hanko, we gather in the mess with the researchers. Maiju Lehtiniemi, the expedition leader, runs through the monitoring that has been carried out and any results that have already been obtained. They managed to collect all of the required samples, the survey equipment remained intact, and there was no GPS interference this time.

As the ship approaches the quay, we go out on deck to greet the researchers who are waiting to come aboard. Some of those who were involved in monitoring the Gulf of Finland will now stay ashore, while others will continue their journey through the Archipelago Sea towards the Gulf of Bothnia.

As strong winds and high waves are forecast for the Bothnian Sea, the Aranda will spend the night berthed in Hanko. Sneaking behind an island to shelter from the wind would also be an option, but it makes more sense to wait awhile and ensure that it’s safe to take samples.

Syke’s coastal monitoring vessel also arrived in Hanko at the same time, and we bump into its employees on the train from Hanko to Karjaa. The results of their coastal monitoring are also nothing to celebrate: all of the surveyed coastal waters were in poor condition with regard to eutrophication – mainly due to nutrient emissions from agriculture and forestry. The oxygen situation has also deteriorated.

Yet in spite of the dire state of the Baltic Sea, we feel tired but happy on the train back to Helsinki. Planning conservation measures would be challenging – if not impossible – without the information provided by professional, long-term monitoring of the state of the Baltic Sea. It also lets us know that the measures we have already taken have eased the plight of the Baltic Sea, that is, we are heading in the right direction. But we still need decision-makers and decisions that will really lean on these research results and help save the Baltic Sea.

Sources and additional information:

Press release of Syke on the monitoring results: Long-term monitoring indicates clear changes in Baltic Sea ecosystem. 28.8.2025.

Finnish Environment Institute: https://www.syke.fi/en