The oil lurking in old shipwrecks poses a major environmental risk

Text

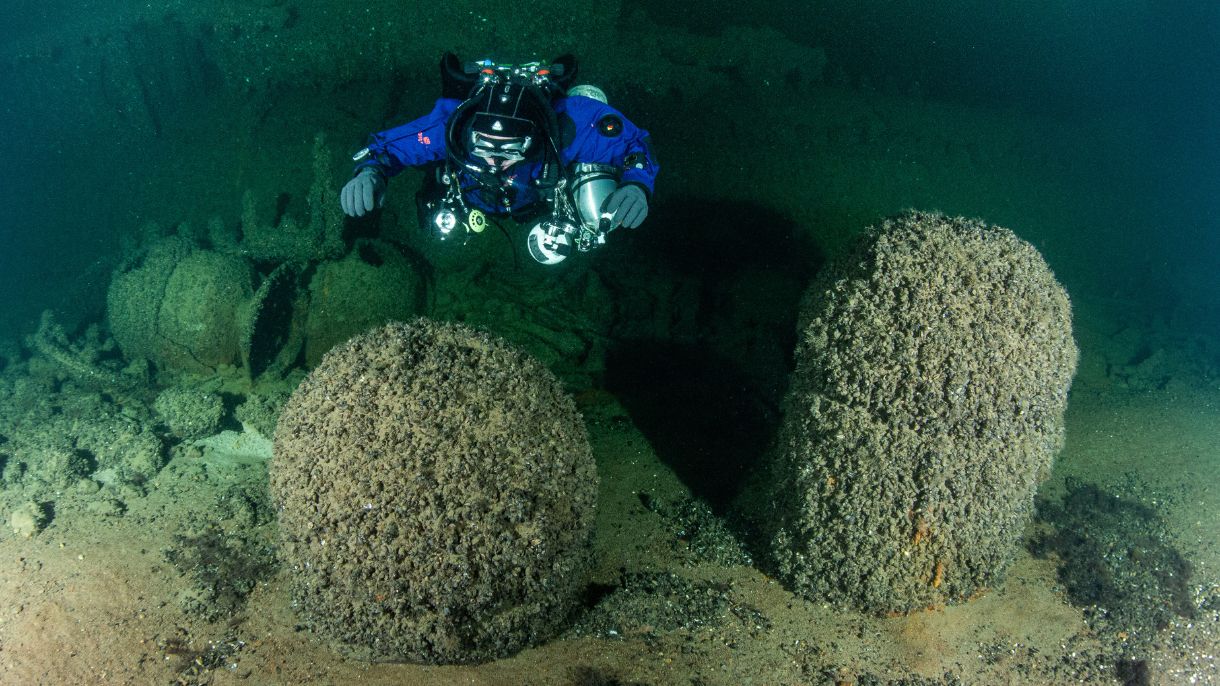

At the bottom of the Baltic Sea rests thousands of old shipwrecks that hold not only fascinating historical stories but also serious environmental risks. Diver and marine biologist Juha “Roope” Flinkman has committed his spare time investigating these wrecks. He has dived to many of the ships that sunk during the first and second world wars, witnessing the oil slicks generating from the wrecks as well as ammunitions that carry the potential of causing substantial destruction.

Now the Baltic Sea’s ecosystem is threatened precisely by the oil lurking in old wrecks.

“During the First World War, the fuel of the war ships was mostly coal, but oil started to become more commonly used in the faster ships”, Flinkman explains.

The greatest risk occurs when the wrecks rust over time, causing the oil to be released into the water. To stop this the oil should be removed and stored from the wrecks. This is a big and expensive operation. Working beneath the surface involves both humans and robots.

”Yet even more expensive is cleaning up the oil that is discharged into the sea and to the beaches. And then the accident has already happened”, Flinkman points out.

One ticking time bomb lies southwest of the Archipelago Sea’s national park, one of the jewels of Finnish nature. The battleship Ilmarinen, sunk during the Continuation War, contains a massive amount of diesel fuel in its tanks – around 100,000 liters. If the oil were to leak into the sea, it would cause irreversible damage to the region’s ecosystems.

“All toxic compounds are quickly dissolved form diesel fuel into the sea water. It does evaporate rather fast, but it is also the most toxic oil possible”, Flinkman tells.

The Finnish Ministry of the Environment is currently examining the possibilities of emptying the tanks of Ilmarinen: the work is supposed to be done during 2025–2026. The threat is somewhat alleviated by the fact that the Border Guard conducts regular surveillance flights over the Baltic Sea, making it easier to detect oil spills. If oil is spotted on the water’s surface, researchers quickly begin investigating its source.

Flinkman says that the risks caused by oil spills have started to be taken more seriously all over the world.

“Very recently, people have woken up to this hidden problem. Wrecks are everywhere, and we are approaching the time when they will rust away. The oils have to be removed before a catastrophe happens.”

The operations of emptying the wrecks usually require having good relations with other countries: the sunken ship found in one’s own territorial waters might not have sailed under the country’s own flag. When the wrecks belong to another country, the operation can only commence with a good mutual understanding with the country that the shipwreck belongs to.

“In the end, it is rather easy among the EU and Nato countries. Understandably, there is reluctance to interfere with the Russian shipwrecks in the current global situation.”, Flinkman explains.

The threat of an explosion

Many of the wrecks from times of war also hide another threat: unexploded ammunition. Torpedos, mines and missiles still rest in the warships and around them, ready to be exploded.

Flinkman explains that the risk of these ammunitions exploding by themselves is very small. However, the risk is always risen when there is aim to explore the wrecks or empty them of oil. Using magnets in the process of emptying oil tanks can activate old ignition systems. This is why clearing explosives has to precede any exploration of the wrecks.

“A sea mine, for instance, includes 200-350 kilos of explosives. This is indeed a big bang”, Flinkman states.

The potential explosion of the ammunition is not only dangerous to the diver. It can also release vast amounts of oil at once, which would lead to serious environmental impacts.

Assessing environmental impacts is very familiar to Flinkman who has pursued a long and impactful career in marine research. He has been responsible for research diving and its development at the Tvärminne Zoological Station of the University of Helsinki, at the Marine Research Institute and at the Finnish Environmental Center.

Flinkman arrives at the interview after his last official sea exploration. Retirement from the Finnish Environmental Center will soon come, and trips on the marine research vessel Aranda will be left behind. He will however not abandon the sea – salt water is in his genes.

”There are many seafarers in my family and my father was a boatwright”, Flinkman says.

He spent his childhood on the family boat, but the sea began to attract him even more during his teenage years. His diving hobby started in his teens when Flinkman had the opportunity to try scuba diving with a friend of his father’s. The interest grew deeper with his studies in marine biology.

In addion to work he spent his spare time at the Baltic Sea. Flinkman is a founding memebr of Badewanne, a non-profit organisation. The divers of the organisation have documented the shipwrecks in the Gulf of Finland for over 20 years.

Flinkman describes diving to be like expedition – each dive has the potential to reveal forgotten events and secrets of the past. Despite this, the dives are not some random adventures: every operation of Badewanne is planned with detail and carried out in a targeted manner.

On top of dives the members of Badewanne do background work related to the wrecks – they study archives and other historical sources. However, the most important piece of the puzzle must be picked from the bottom of the Baltic Sea. The wrecks always tell the last chapter of the story. The questions about the fate of ships lost in wars and the people who were aboard them are finally answered when Flinkman and their team bring them to the surface from their dives.

The article was first published in Finnish in John Nurminen Foundation’s magazine Telegrammi (2/2024).

Dive into the wrecks of wartime

The Fog of War – The First World War in the Gulf of Finland, takes the reader aboard on expeditions on the wrecks lying on the depths of the sea, revealing forgotten stories of events that occurred over a hundred years ago. The writers Juha Flinkman and Jouni Polkko combine the historical combats and archives with the fascinating research made by Badewanne’s scuba diving team. The stories of shipwrecks unfold through stunning underwater images, and archival photos from World War I of ships, submarines, and people illustrate historical moments.

The Fog of War exhibition recounts the dramatic events that took place during the First World War in the Gulf of Finland, exploring the hidden mysteries of historical wrecks lying on the seabed. What do the steamships Alice H and Houtdijk, which sank a hundred years ago, look like? What caused the armored cruiser Pallada to sink? Visit our exhibition to find out!